Gene Discovery, Transformation and Genomic Applications 2025

Application of the Dominant Allele TaCol-B5 for Higher Yield in Winter Wheat Breeding

We discovered and cloned the TaCol-B5 gene, which controls the number of spikelets per spike, using a map-based cloning approach. We demonstrated that the dominant allele, TaCol-B5, increases spikelet number, spike length and field-based grain yield in transgenic wheat plants. A Kompetitive Allele-Specific PCR (KASP) marker was developed to detect the single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) responsible for the critical Ser269/Gly269 substitution distinguishing the dominant TaCol-B5 from the recessive Tacol-B5 allele.

The availability of the TaCol-B5 sequence and KASP marker provides an unprecedented opportunity to deploy this allele in wheat breeding programs worldwide. By screening over 141 Triticum turgidum and 3,859 T. aestivum accessions, including landraces and cultivars from diverse regions, we identified 106 lines carrying the dominant TaCol-B5 allele, distributed across 23 countries.

This favorable allele is more frequent in Africa and the Americas but occurs in only 2.7% of global accessions, a frequency similar to that reported in our previous “Science” publication. Among historic and modern hard red winter wheat varieties used in the OSU breeding program, only Billings and Baker’s Ann carry the dominant TaCol-B5 allele, while Skydance – the closely related half-sibling of Baker’s Ann – does not.

We have extensively used Billings and Baker’s Ann and their descendants as parents in the OSU WIT breeding populations. However, preliminary results from a former master’s student indicated that there was no significant yield effect of TaCol-B5 in these populations. To investigate the underlying mechanism of TaCol-B5 repression in winter wheat, several experiments were conducted:

- Cross-environment validation: In collaboration with a former visiting scholar, we retested transgenic spring wheat (Yangmai18) expressing TaCol-B5 cDNA under the Ubiquitin promoter. TaCol-B5 significantly increased spike length, spikes per plant, spikelets per spike and grain yield in a second environment (Figure 1A), confirming its effects across locations.

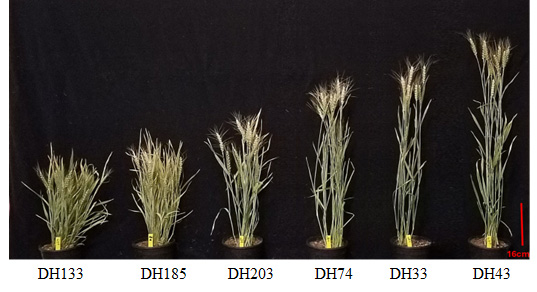

Figure 1a. Phenotypic effects of TaCol-B5. Transgenic spring wheat in the field location. - Doubled haploid (DH) population analysis: The Duster × Billings DH population grown under controlled conditions at Stillwater showed quantitative variation in plant height, spike number and spikelets per spike (Figure 1B). However, these traits were not associated with the TaCol-B5 allele from Billings or the Tacol-B5 allele from Duster, supporting the hypothesis that TaCol-B5 activity is repressed in winter wheat backgrounds.

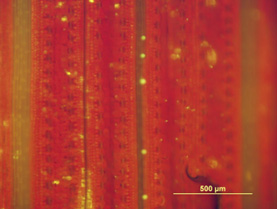

Figure 1b. Phenotypic effects of TaCol-B5. Segregation of natural TaCol-B5/Tacol-B5 in the Duster x Billings DH population tested in the greenhouse at Stillwater. - Native promoter expression: Using the native TaCol-B5 promoter, we expressed genomic TaCol-B5 fused with the YFP (yellow fluorescent protein) gene in Yangmai18. Two T₁ families (#126 and #132) exhibited segregation for plant height and grain yield, confirming functional effects of the native promoter-driven TaCol-B5 (Figure 2A). Fluorescence was detected in leaves using a standard fluorescence microscope (Figure 2B) and in the apex using a Zeiss confocal microscope (Figure 2C), demonstrating that TaCol-B5 retained its biological activity when fused to YFP.

Figure 2a. Phenotypic effects of TaCol-B5 driven by its native promoter. Comparison of TaCol-B5 effects between transgenic, non-transgenic and wildtype plants.

Figure 2b. Phenotypic effects of TaCol-B5 driven by its native promoter. The YFP fluorescent signals in the leaf epidermal surface of transgenic plants under standard fluorescent microscopy.

Figure 2c. Phenotypic effects of TaCol-B5 driven by its native promoter. The YFP fluorescent signals in the apex of transgenic plants under confocal fluorescent microscopy. - Transformation of winter wheat: Using the same native promoter construct, we transformed the winter wheat cultivar Paradox and obtained two T₀ plants. These TaCol-B5–YFP transgenics will facilitate direct identification of downstream DNA/RNA targets through magnetic protein–RNA (MPR) pull-down assays and protein interactors through magnetic protein–protein (MPP) pull-down assays. These assays, widely applied in both plant and human studies, will allow us to identify repressors of TaCol-B5 in winter wheat cultivars, which will be pursued in the next Oklahoma Wheat Research Foundation funding cycle.

Once repressors are identified, we will screen for natural null alleles or EMS-induced mutants and introduce them into local cultivars. Alternatively, CRISPR/Cas9 will be used to disrupt repressor genes. The cloned TaCol-B5 gene has been widely cited, and its cloning marks the beginning of a new phase in which this gene is being integrated into yield regulatory networks. Our ongoing work aims to elucidate TaCol-B5 functions across genetic backgrounds, identify interacting yield genes and develop molecular tools to enhance breeding efficiency. The impact will be direct and far-reaching, as deployment of TaCol-B5 through conventional breeding for non-transgenic wheat cultivars ensures minimal resistance and broad adoption.

Deployment of HaHB4 in Winter Wheat

Despite decades of research and the identification of thousands of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for abiotic stress, no single gene has been cloned or deployed for drought tolerance in wheat. This gap underscores the pressing need for innovative strategies that surpass conventional breeding methods. One such strategy involves the sunflower transcription factor HaHB4, which has been engineered into wheat to enhance drought resilience. Transgenic HaHB4 wheat has gained regulatory approval in Argentina and Brazil and is progressing toward food and feed approvals worldwide. In the United States, the FDA deemed HaHB4 wheat safe in 2022, and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture deregulated the trait in 2024. However, the available HaHB4 wheat cultivar (Cadenza) is a spring wheat unsuitable for the Great Plains due to its dominant Vrn-A1a allele. Cadenza was released to the United Kingdom market in 1995. Introgressing HaHB4 into winter wheat by crossing would take years to decades, while direct transformation of adapted cultivars could accelerate deployment.

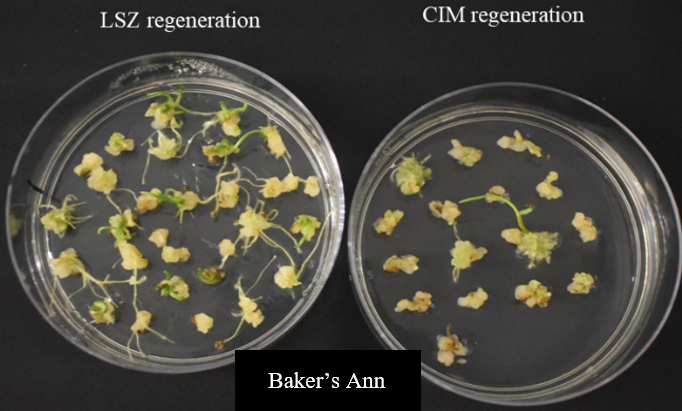

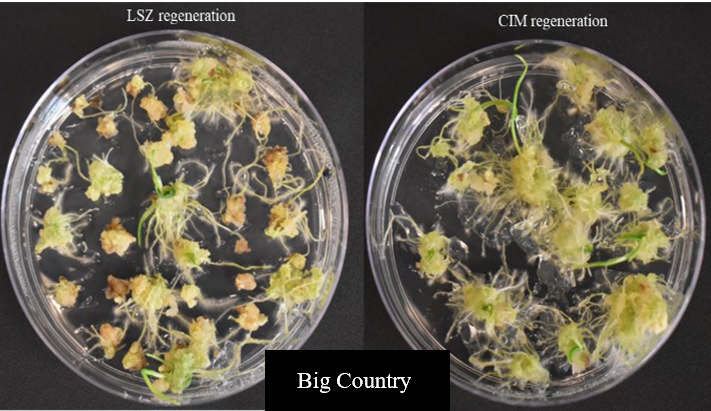

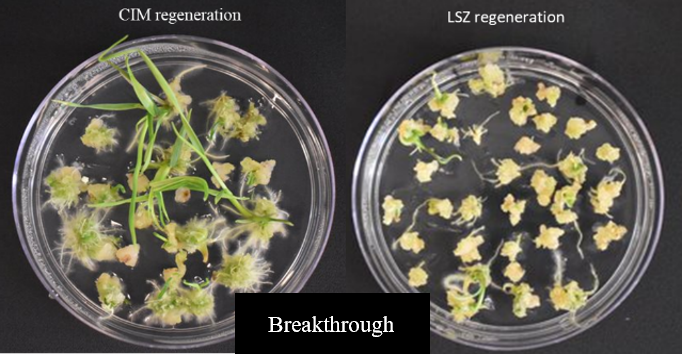

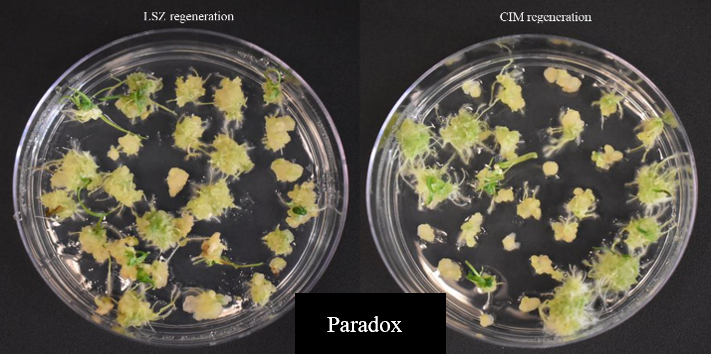

We have evaluated 14 locally adapted winter wheat cultivars using two modified regeneration protocols. The cultivars included Baker’s Ann, Big Country, Billings, Breakthrough, Butler’s Gold, Duster, Gallagher, Jagger, Paradox, Showdown, Skydance, Strad CL+, Tam112 and Uncharted, depending on embryo availability. Immature embryos were collected from field-grown plants, although access to embryos during the off-season may present challenges. Results indicated that Baker's Ann, Big Country, Breakthrough and Paradox could regenerate on LSZ medium, CIM medium or both (Figure 3). Due to different hormone composition, the two plant tissue culture media enable callus formation or shoot regeneration.

Figure 3a. Regeneration of local winter wheat cultivars on LSZ medium (left) and CIM medium (right) - Baker's Ann.

Figure 3b. Regeneration of local winter wheat cultivars on LSZ medium (left) and CIM medium (right) - Big Country.

Figure 3c. Regeneration of local winter wheat cultivars on LSZ medium (right) and CIM medium (left) - Breakthrough.

Figure 3d. Regeneration of local winter wheat cultivars on LSZ medium (left) and CIM medium (right) - Paradox.

We selected the cultivar Paradox in the preliminary experiment. Paradox is a hard red winter wheat (HRW) variety released by Oklahoma State University in early 2023, developed with the aid of molecular markers for the Bx7oe high-molecular-weight glutenin subunit. Importantly, flour from Paradox is already used by the milling industry as a proprietary alternative to additives, such as dough conditioners. We have obtained two T₀ plants. These transgenics will facilitate direct characterizations and deployment of HaHB4 effects in winter wheat cultivars.

Additional concerns on the HaHB4 transgenic wheat are the pleiotropic effects of HaHB4 driven by the maize UBI promoter, which has been associated with delayed flowering, reduced stem thickness and fewer tillers. A BLAST search of the TraesCS5A02G316800 protein sequence against the NCBI ClusteredNR database revealed the highest similarity to Arabidopsis thaliana homeobox 7 and homeobox 12 proteins, and the closest characterized hit in rice was HD-ZIP protein HOX6 (Oryza sativa Japonica; NP_001409841). None of these Arabidopsis or rice homologues have been functionally characterized.

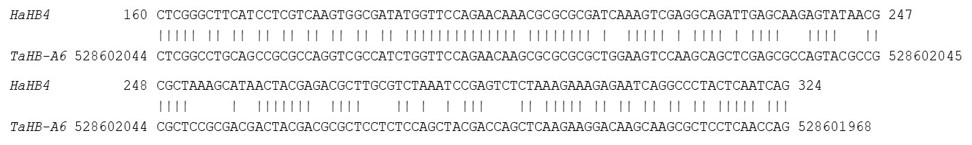

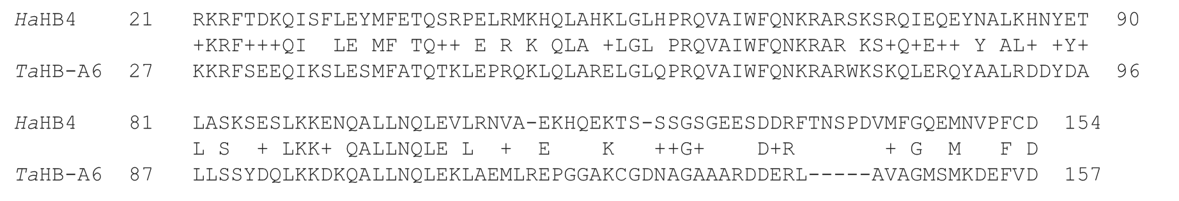

We used the sunflower HaHB4 cDNA sequence to query the wheat genome database and identified a single homoeologous triad on chromosome group 5 with significant DNA-level identity to HaHB4. Sequence analysis showed that HaHB4 shares 68.5% identity with TraesCS5A02G316800 (5A; E = 3.06 × 10⁻⁷), 75% identity with TraesCS5B02G317400 (5B; E = 1.07 × 10⁻⁷), and 68.5% identity with TraesCS5D02G323100 (5D; E = 3.06 × 10⁻⁷). Each of these wheat genes consists of two exons and one intron, with the sequence similarity to HaHB4 localized within the first exon. Sequence alignment confirmed that TaHB6 proteins are most likely homologs to HaHB4 (Figure 4). The three wheat proteins are provisionally designated as TaHB-A6, TaHB-B6 and TaHB-D6.

We analyzed the sequences of TaHB-A6, TaHB-B6 and TaHB-D6 across ~30 wheat cultivars included in wheat pangenome sequencing efforts, encompassing more than 10 global cultivars curated by the Germplasm Unit at the John Innes Centre in the United Kingdom, as well as 17 Chinese cultivars representing the country’s breeding history and genomic changes. No allelic variation was detected in the coding regions of the three homoeologous genes. This lack of natural variation highlights the need for a transgenic approach to elucidate the functions of the TaHB6 genes and their potential role in drought tolerance. We have initiated the experiments on TaHB-A6, TaHB-B6 and TaHB-D6 in wheat. By conducting side-by-side comparisons between HaHB4 and TaHB6, we will reveal whether native wheat pathways can substitute for foreign solutions and provide a practical route to enhance yield stability in U.S. wheat.

Figures 4a-b. Comparison of the DNA and protein sequences between the sunflower HaHB4 and wheat TaHB-A6.

Figure 4a. Comparison of the HaHB4 cDNA and TaHB-A6 exon 1 sequences. TaHB-A6 is used as an example of three homoeologous genes in wheat.

Figure 4b. Comparison of the protein sequences between HaHB4 and TaHB-A6. The protein sequence was deduced from its coding region.

Editing of Genes Leading to Herbicide Tolerance in Wheat

We have obtained two new T0transgenic plants targetingPSB and VLCFA genes. The identification of editing events in these genes is underway. Additionally, in collaboration with Dr. Liberty Galvin, we have designed experiments to phenotype the EMS-induced lines that exhibit the mutated target, and two natural cultivars – Mace from Australia and Selbu 2.0 from Washington State University – may possess natural alleles in the target genes.