Wheat Pathology Report for 2025

Disease evaluations of 2025 OSU Wheat Breeding Lines

In 2025, we evaluated 315 Oklahoma State University wheat breeding lines for their responses to five fungal diseases: leaf rust, stripe rust, powdery mildew, tan spot and septoria nodorum blotch (Table 1). Evaluations against leaf rust, powdery mildew and tan spot were conducted in the greenhouse using artificial inoculations, whereas evaluations against septoria nodorum blotch and stripe rust were performed in the field. Across these tests, a total of 23,475 disease data points were collected. Greenhouse and field evaluations will continue to support the advancement of breeding lines with improved disease resistance in the OSU wheat breeding program.

| Disease | Test Condition | Number of breeding lines - Seedling Stage | Number of breeding ines - Adult-plant Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf rust | Greenhouse | 315 | 315 |

| Powdery mildew | Greenhouse | 315 | 315 |

| Tan spot | Greenhouse | 190 | - |

| Septoria nodorum blotch | Field | - | 190 |

| Stripe rust | Field | - | 242 |

Understanding the genetic factors underlying stripe rust resistance in the OSU hard red winter wheat cultivar Baker’s Ann

Baker’s Ann (released in 2018, PV 201900172, pedigree: TX00D1390/OK03522) has consistently exhibited high levels of stripe rust resistance at the adult plant stage since 2014 and has been widely used in OSU’s wheat breeding program for its stripe rust resistance and premium milling and baking qualities. In contrast, seedling evaluations against United States stripe rust pathogen races revealed susceptibility, confirming the absence of effective seedling or all-stage resistance genes. Thus, stripe rust resistance in Baker’s Ann is attributed exclusively to adult plant resistance genes.

To dissect the genetic basis of Baker’s Ann resistance, a doubled-haploid (DH) population of 125 lines from the cross OK12D22004-016 × Baker’s Ann was evaluated for stripe rust response at the adult plant stage in the greenhouse and in field trials conducted in Oklahoma, Kansas and Washington. In contrast to Baker’s Ann, OK12D22004-016 shows moderate susceptibility to stripe rust across the U.S. Great Plains. We applied genotyping-by-sequencing, which generated 7,268 polymorphic single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers for this DH population.

Genetic mapping using the phenotypic and genotypic data of the 125 DH lines showed that stripe rust adult plant resistance in Baker’s Ann is attributed to four genomic regions (loci) located on chromosome arms 2DL, 4BS, 4BL and 7BL. There were two major loci detected in Baker’s Ann across multiple environments in Oklahoma, Kansas and Washington: QYr.osu-2DL (Figure 1), which explained up to 57% of the phenotypic variation and mapped near the stripe rust resistance gene Yr54 and QYr.osu-4BL, which explained up to 15% of the phenotypic variation and mapped near the resistance gene Yr62. As QYr.osu-2DL explained the highest phenotypic variation in Baker’s Ann, we developed five breeder-friendly Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP) markers, KASP_S2D_636865313, KASP_S2D_649277571, KASP_S2D_650730433, KASP_S2D_651572347 and KASP_S2D_652727251; Figure 1), which can be used in marker-assisted selection.

Figure 1. The genetic effect and chromosomal location of QYr.osu-2DL in the OK12D22004-016 × Baker’s Ann doubled-haploid population. Red rectangles indicate the genomic region of the locus QYr.osu-2DL. Highlighted markers correspond to the flanking markers QYr.osu-2DL. Red dashed lines on logarithm of the odds (LOD) curves indicate the significance threshold. IT = Infection type (0-9 scale with 9 being the most susceptible); DS = Disease severity (%); GH = Greenhouse (temperature 4–20°C); CH = Chickasha, OK; RS = Rossville, KS; PL = Pullman, WA; MV = Mount Vernon, WA; BLUE = multi-environment best linear unbiased estimates across field environments. The numbers 1 and 2 after the location names indicate first and second disease ratings at different dates.

Genome-wide association mapping identified genomic regions associated with stripe rust response at the adult-plant stage in hard winter wheat

We created a germplasm collection of 619 breeding lines and cultivars. In this panel, there were 565 breeding lines from the OSU wheat breeding program and 54 historical cultivars from the OSU and Kansas State University wheat breeding programs. This collection was evaluated at the seedling stage in the greenhouse against stripe rust pathogen isolates collected from Oklahoma fields; however, the percentage of resistant and moderately resistant lines was only 3%. In contrast, stripe rust field evaluations at the adult-plant stage in Oklahoma, Kansas and Washington state showed a high percentage of lines that were resistant. For instance, 42-77% of the germplasm showed highly resistant infection types, depending on field environments. Higher frequencies of resistant lines were observed in the Great Plains (Oklahoma and Kansas) compared to Washington. This is due to the higher pathogen virulence diversity and favorable environmental conditions for the disease development in Washington.

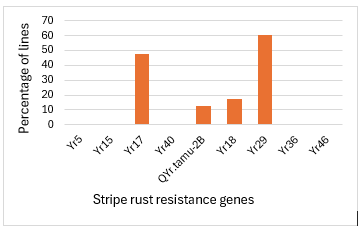

This germplasm was genotyped using genotyping by sequencing, and 34,357 SNP markers were generated. This panel was also genotyped using molecular markers linked to five known all-stage stripe rust resistance genes (Yr5, Yr15, Yr17, Yr40 and QYr.tamu-2B) and four adult plant stripe rust resistance genes (Yr18, Yr29, Yr36 and Yr46) (Figure 2). The all-stage resistance genes Yr17 and QYr.tamu-2B were identified in 48% and 13%of this germplasm, respectively. However, most U.S. stripe rust pathogen isolates are virulent to these two genes. Although Yr17 on the 2NvS/2AS translocation is not effective at the seedling stage, it was found to be linked to a high-temperature adult plant resistance gene, so it is beneficial to keep this translocation in the hard winter wheat breeding pipeline. The adult plant stripe rust resistance genes Yr18 and Yr29 were found in 17% and 61%, respectively.

Figure 2. Frequencies of stripe rust resistance (Yr) genes in 619 hard winter wheat breeding lines and cultivars based on molecular markers.

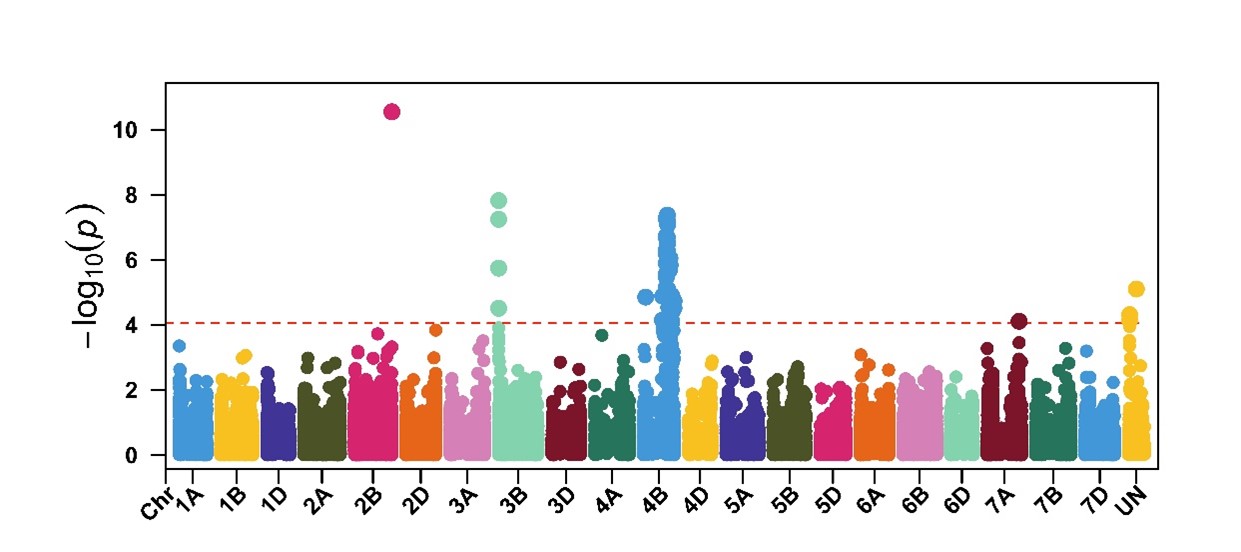

Stripe rust field data and genotypic data were used for genome-wide association mapping (GWAS) to identify genomic regions associated with stripe rust resistance in this germplasm. The GWAS identified 129 genomic regions associated with stripe rust response at the adult plant stage, of which two major loci on chromosome arms 3BS and 4BL were consistently identified across field environments using multiple GWAS models (Figure 3). The locus on chromosome 3BS was found within the genomic regions of the adult plant resistance genes Yr30 and Yr58. Further work is needed to determine the relationship between these genes and the locus we identified on chromosome 3BS. Yr62 and Yr68 were the only characterized adult plant resistance genes on chromosome 4BL. However, they were mapped far (16-54 million base pairs) from our identified locus on chromosome 4BL. To deploy this resistance source in wheat breeding, KASP marker KASP_S4B_524362674 was developed. Based on this marker, this resistance source on chromosome 4BL is present in 27% of the hard winter wheat germplasm.

Figure 3. Genome-wide association mapping identified a genomic region on chromosome 4BL that was associated with stripe rust response across multiple field environments in Oklahoma, Kansas and Washington.

Determine sensitivity genes to Septoria nodorum blotch in hard winter wheat

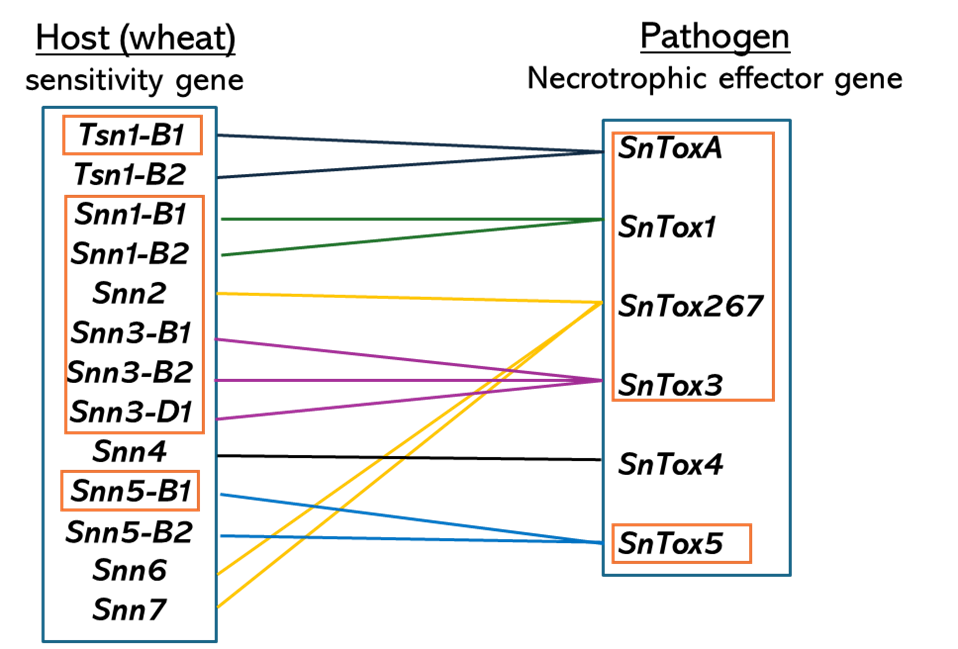

Septoria nodorum blotch (SNB), caused by Parastagonospora nodorum, is a fungal disease that can cause leaf blotch and glume blotch. In Oklahoma, this disease has become a challenge to wheat production since 2019. However, very little is known about SNB resistance/sensitivity genes in hard winter wheat. The recognition of P. nodorum necrotrophic effectors (NEs) by wheat sensitivity genes leads to host susceptibility (Figure 4). To date, the sensitivity genes Tsn1-B1, Snn1-B1, Snn-B2, Snn2, Snn3-B1, Snn3-B2, Snn3-D1 and Snn5-B1 and the NE genes SnToxA, SnTox1, SnTox3, SnTox5 and SnTox267 have been cloned. Our objectives were to evaluate the germplasm of 619 hard red winter wheat breeding lines and cultivars for sensitivity to five cloned NEs and five Oklahoma P. nodorum isolates. We have also conducted GWAS to validate the presence of known sensitivity genes and identify possibly novel SNB sensitivity/resistance genes.

Figure 4. Wheat sensitivity genes and Parastagonospora nodorum necrotrophic effector genes interactions. Genes in orange boxes were cloned.

Necrotrophic effector infiltration assays showed that 54%, 2%, 37%, 13% and 15% of the breeding lines and cultivars were sensitive to SnToxA, SnTox1, SnTox3, SnTox267 and SnTox5, respectively. This suggests that the sensitivity genes interacting with the NEs Tsn1-B1, Snn1-B1, Snn3-B1/Snn3-B2, Snn2 and Snn5-B1 were present in 54%, 2%, 37%, 13% and 15%, respectively. The reactions of some hard red winter wheat cultivars in this panel to these five NEs are illustrated in Table 2. Eliminating these sensitivity genes, especially those present in high frequencies, should reduce the frequency of SNB susceptibility in the breeding pipeline.

| Cultivar Name | SnToxA | SnTox1 | SnTox3 | SnTox267 | SnTox5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bentley | I | I | I | I | I |

| Big Country | I | I | I | I | I |

| Breakthrough | S | S | S | I | S |

| Doublestop CL+ | S | I | I | I | S |

| Duster | S | I | I | S | I |

| Firebox | S | I | I | I | I |

| Gallagher | S | I | I | S | I |

| Green Hammer | I | I | I | I | I |

| High Cotton | S | I | I | I | I |

| Iba | S | I | I | S | I |

| Jagger | S | I | I | I | S |

| OK Corral | I | I | S | I | I |

| Orange Blossom CL+ | I | I | S | I | I |

| Paradox | S | S | I | S | I |

| Ruby Lee | S | I | I | I | I |

| Showdown | S | I | I | I | I |

| Smith's Gold | S | I | S | I | I |

| Spirit Rider | I | I | I | S | I |

| Uncharted | I | I | I | I | I |

I: Insensitive to the necrotrophic effector (resistant reaction); S: Sensitive to the necrotrophic effector (susceptible reaction)

Tsn1 was found to consistently contribute to susceptibility to all five P. nodorum isolates, which carry the NE SnToxA. Therefore, eliminating Tsn1 from OSU wheat using molecular markers should enhance resistance to SNB. Tsn1 causes susceptibility to two other fungal diseases: tan spot and spot blotch. Therefore, eliminating Tsn1 will enhance resistance against these three diseases.

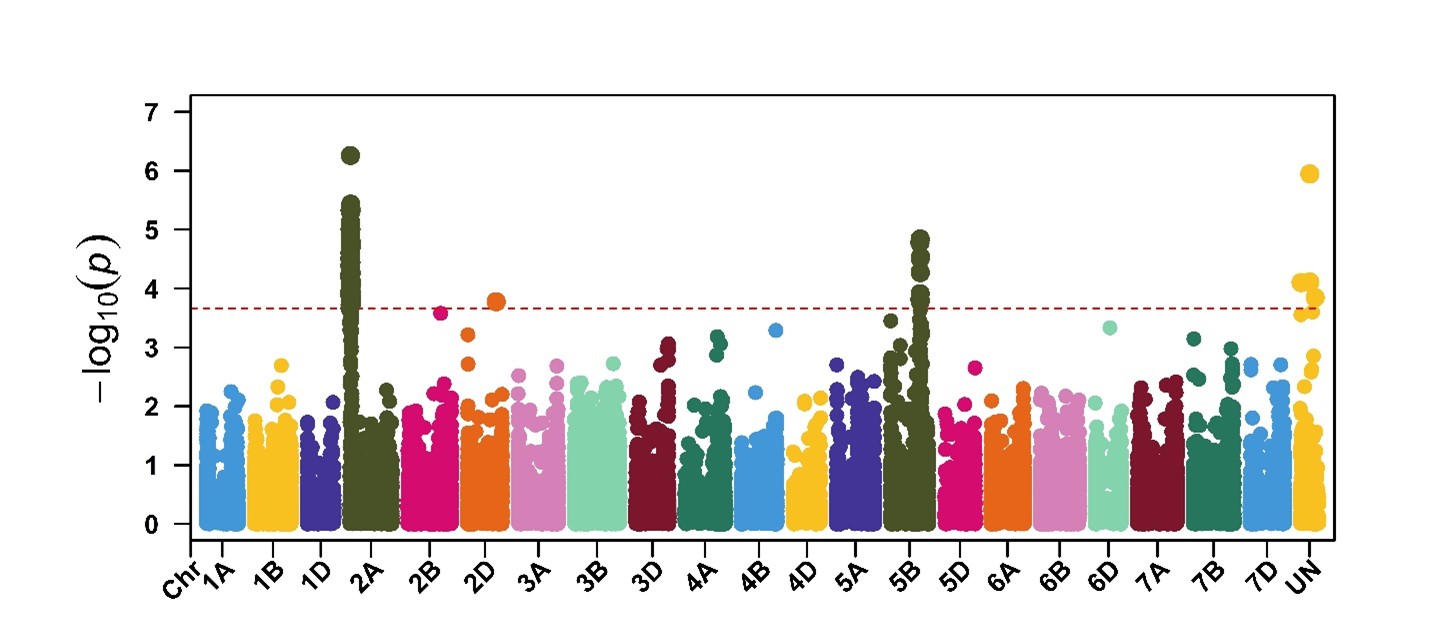

GWAS confirmed the presence of the sensitivity genes Tsn1-B1, Snn1-B1, Snn2, Snn3-B1/Snn3-B2 and Snn5-B1 in this germplasm. In addition to these known sensitivity genes in wheat, GWAS identified other unknown loci associated with responses to P. nodorum isolates and NEs. This suggests that other SNB resistance/susceptibility genes must be present, including a novel locus (designated here as Qsnb.osu-2AS. Qsnb.osu-2AS) located on chromosome arm 2AS was found to be associated with responses against four of the five isolates tested in this study. This locus plays a major role in SNB resistance/susceptibility in addition to the sensitivity gene Tsn1 located on chromosome arm 5BL (Figure 5).

Figure 5. GWAS showing significant markers associated with response to P. nodorum isolate OKG16Sn-16. The peak on chromosome 2A corresponds to the locus Qsnb.osu-2AS, whereas the peak on chromosome 5B corresponds to the sensitivity gene Tsn1.