OSU scientist uncovering the mystery of microbes in plant immunity

Thursday, October 13, 2022

Media Contact: Alisa Boswell-Gore | Agricultural Communications Services | 405-744-7115 | alisa.gore@okstate.edu

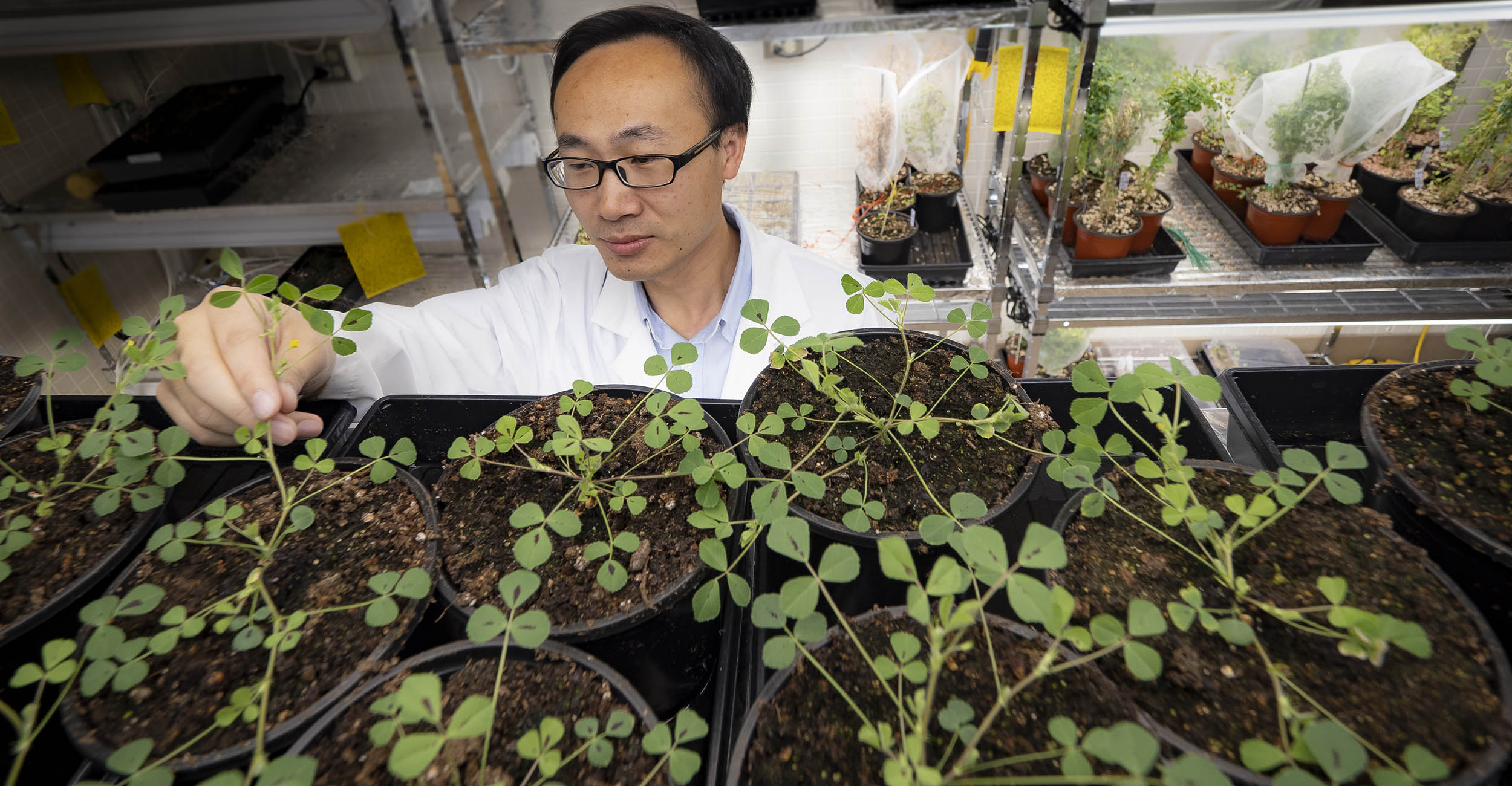

An Oklahoma State University scientist is studying how beneficial microorganisms are to helping plants acquire nutrients.

Through an almost $1 million grant from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Feng Feng — assistant professor in the OSU Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology — will study the interactions between plants and beneficial microorganisms.

The microbes infect plant roots to establish a mutually beneficial relationship with the plant called symbiosis. This relationship provides plants with essential nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus.

Much like people, plants are naturally exposed to a wide variety of microorganisms, some good and some bad, and they have an immune system that triggers defense responses to limit infection. To establish this symbiotic relationship with plants, microbes suppress a plant’s immune system.

Feng said the microbes can produce signal molecules called lipo-chitooligosaccharides (LCOs). The LCOs are recognized by a plant receptor called NFP, and it is this recognition that triggers symbiosis, which hinders the plant’s immunity to infection.

“What we want to know now is how do microbes use LCOs to hinder immunity for plant infections?” Feng said.

Feng and his colleagues at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom will work on a legume species called Medicago truncatula along with barley to understand the molecular process that causes root microbes to suppress immune systems in plants.

“The underlying molecular mechanisms that regulate plant immunity during early symbiotic infection are still largely unclear,” he said. “This project aims to identify a set of plant genes that are required for LCOs to suppress plant immune systems.”

Once the genes have been identified in Medicago truncatula, Feng and his colleagues hope to place them into barley to determine if they enhance the plant’s ability to take in soil nutrients and fight Fusarium graminearum, a fungal disease that causes head blight in small-grain cereals.

“Our research might also bring new insights into engineering nitrogen-fixing symbioses into cereal crops, an important approach to sustaining cereal yields and reducing dependence on inorganic fertilizers,” Feng said.

This material is based upon work supported by the AFRI Competitive Grant under award number 2022-67014-38607 for $916,258 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.