Horticulture specialist researching soilless media and biochar for crop production

Wednesday, November 12, 2025

Media Contact: Alisa Gore | Office of Communications & Marketing, OSU Agriculture | 405-744-7115 | alisa.gore@okstate.edu

An Oklahoma State University food crop expert is studying alternatives to peat moss in commercial and domestic vegetable crop production.

While peat is a common soilless media used for its ability to retain water and nutrients, it is also expensive because of the lengthy and extensive process required to obtain it. Peat is an organic material composed of partially decomposed plant matter that accumulates in wet environments like bogs over thousands of years.

“There has been a huge effort to improve sustainability in the green industry, and one of those efforts is to move away from peat moss, which holds water the best,” said Dr. Tyler Mason, assistant professor and urban horticultural food crop production systems Extension specialist. “But how it is produced and the time it takes to develop raise the question of whether it should be used. The industry uses a backhoe to extract the peat moss from areas that would otherwise remain undisturbed.”

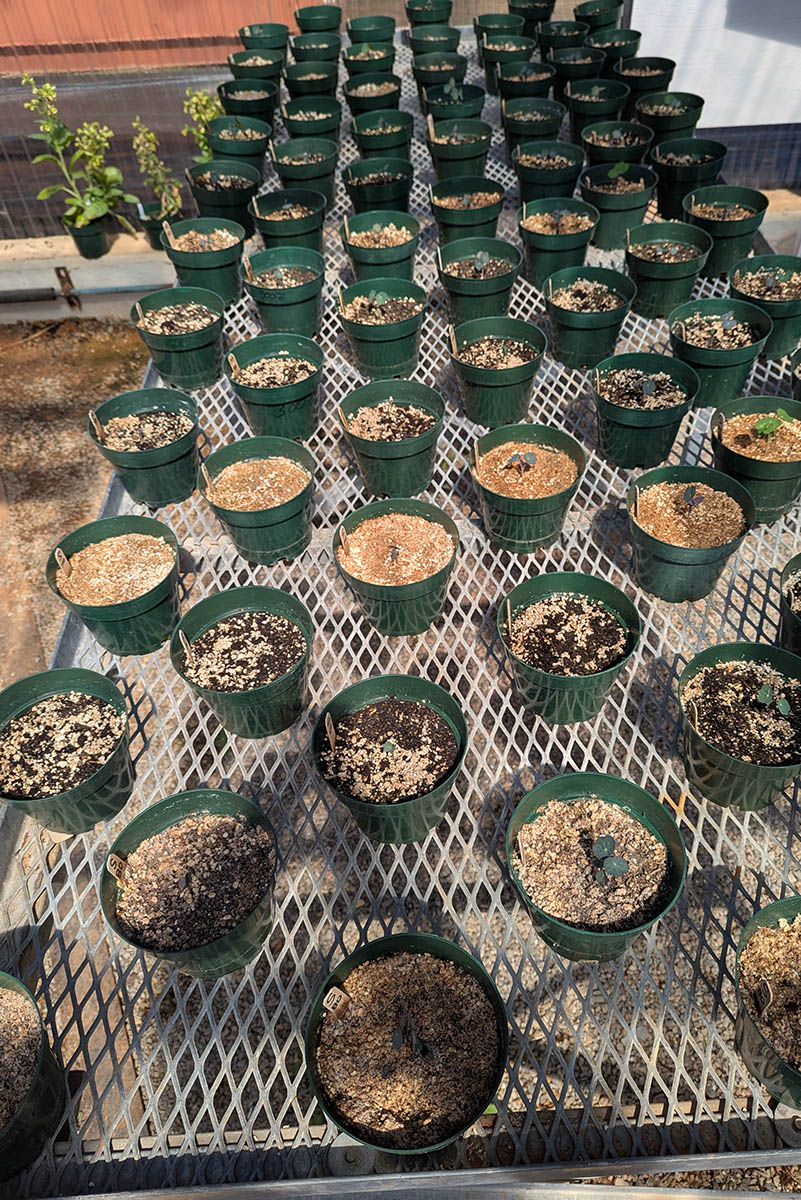

Mason and master’s student Kristal Casey are evaluating ground-up hemp waste as a soilless alternative to peat for growing the edible flower nasturtium.

Mason and master’s student Sathvika Vurelli, along with other OSU scientists, are investigating biochar as a possible addition to soil for growing flowers, turfgrass, peppers and watermelons. Much like compost, biochar is created from various types of organic waste, including eastern red cedar trees, mulch and other carbon-based sources.

“We’re interested in biochar that comes from eastern red cedar trees because it’s an invasive tree in our state,” Mason said. “We’re working to turn an invasive species into a usable product.”

The goal of both projects is to improve the sustainability and soil quality of Oklahoma horticulture crops. Mason is examining the health and water-holding capacity of hemp waste, as well as its compactness.

“If we water on Monday, the peat needs to be watered again on Thursday, but the hemp-based media doesn’t need water until Saturday. That’s an opportunity for water savings,” Mason said.

Past research has demonstrated that biochar enhances the efficiency of nutrient use in crops, as well as the quality of the soil.

“I wanted to know, if I apply biochar at a commonly applied rate of 2,000 pounds per acre and a high rate of 6,000 pounds per acre, do I get a higher yield in peppers, and is there an opportunity for water savings?” Mason said.

Dr. Bruce Dunn, professor of horticulture, is studying how biochar works with flower crops, and Dr. Charles Fontanier, associate professor of horticulture, is growing turfgrass in biochar. Mason is researching the use of this soilless media with Italian-style roasting peppers and seedless watermelons. Mason’s undergraduate student, Makayla Friend, is studying the impact of biochar and brewer’s spent grain at 10% and 20% replacement for peat with growing kale and perennial aster.

Determining the level of success for these products will take two years or more, according to Mason, who said the next steps will be studying the data from the first year of research to see if there was a yield decline with the reduced irrigation treatments or if the biochar fixed that problem.

“This is an exciting next step in the investment to improve soil quality in commercial and local vegetable crop production systems,” Mason said.