Precision Nutrient Management Program 2022

In the past seven years, two things have become very evident from the research performed by the Wheat Improvement Team regarding nitrogen (N) application and utilization of grain only winter wheat.

First, the optimum application timing of nitrogen is between green-up and two weeks post jointing. Pre-plant nitrogen has little value in an October-November sown winter wheat system.

Second, there are significant difference in the uptake of nitrogen (N) between varieties like Gallagher and Green Hammer, the difference being Gallagher concludes N update much earlier in the crop cycle than Green Hammer, which continues significant N uptake post flowering. However, this second and more recent finding is creating questions regard the first findings. The timing studies have been performed almost exclusively on varieties that are similar in their uptake pattern, such as Doublestop CL Plus.

Therefore, the 2021-2022 research plan was to perform a deep dive into the relationship between G (genotype) and N management. The objective was to better understand the influence of genetics on optimum application timing of nitrogen (N). This research was divided between two projects. The first study was designed to evaluate the response of two cultivars – Gallagher and Green Hammer – to N applied across three timings: preplant, greenup and jointing. The rationale was that a difference in preferred N management timing may occur between these two cultivars with differing uptake patterns. N was applied at a rate of 90 lbs per acre across a combination of these three timings. Also included was a 0 N check and a high N rate (140 lbs N/ac) applied at either preplant, greenup or jointing to determine base level and yield potential, respectively. Due to N uptake differences of the cultivars, it was hypothesized the optimum N application timing would differ.

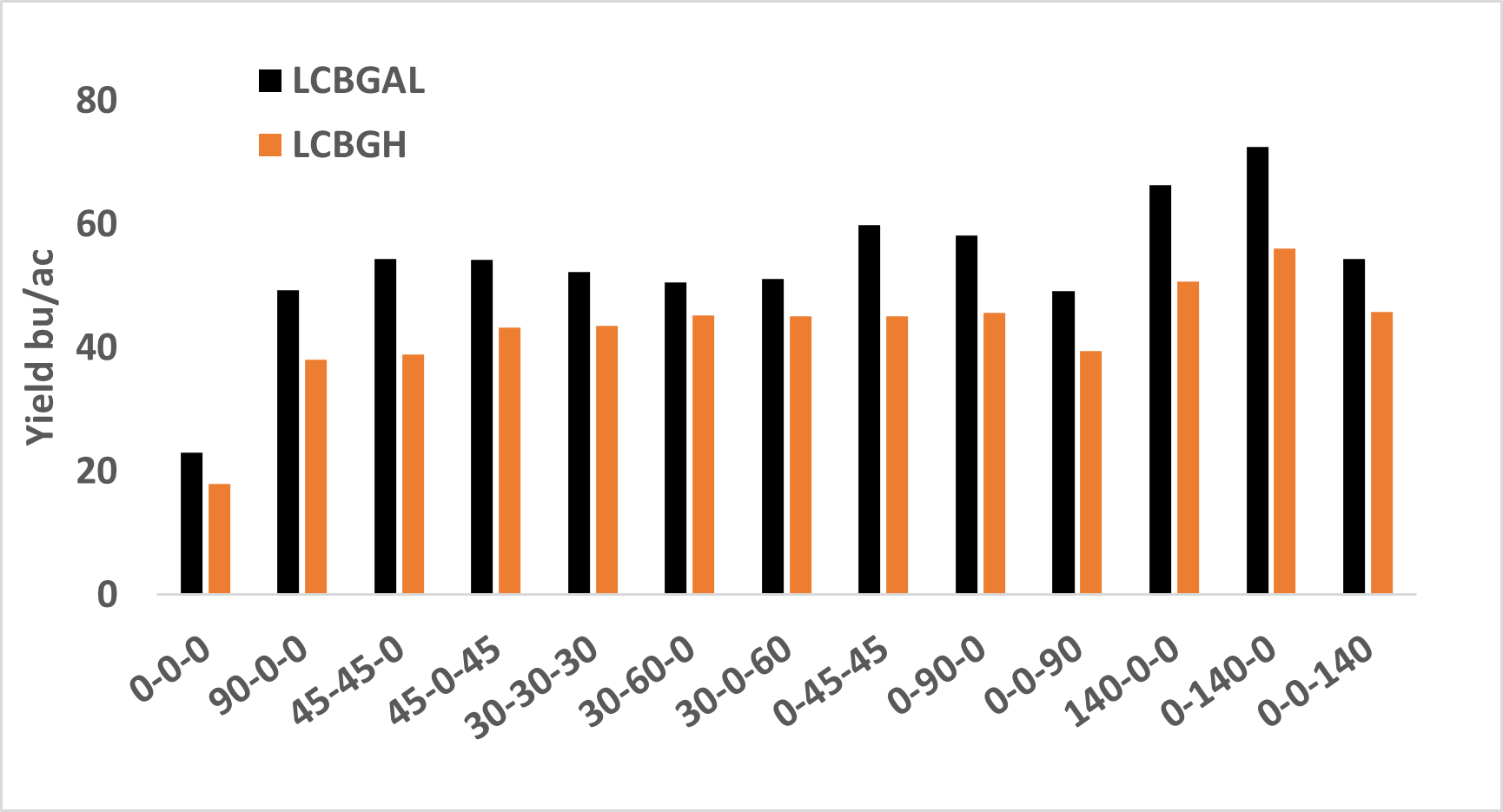

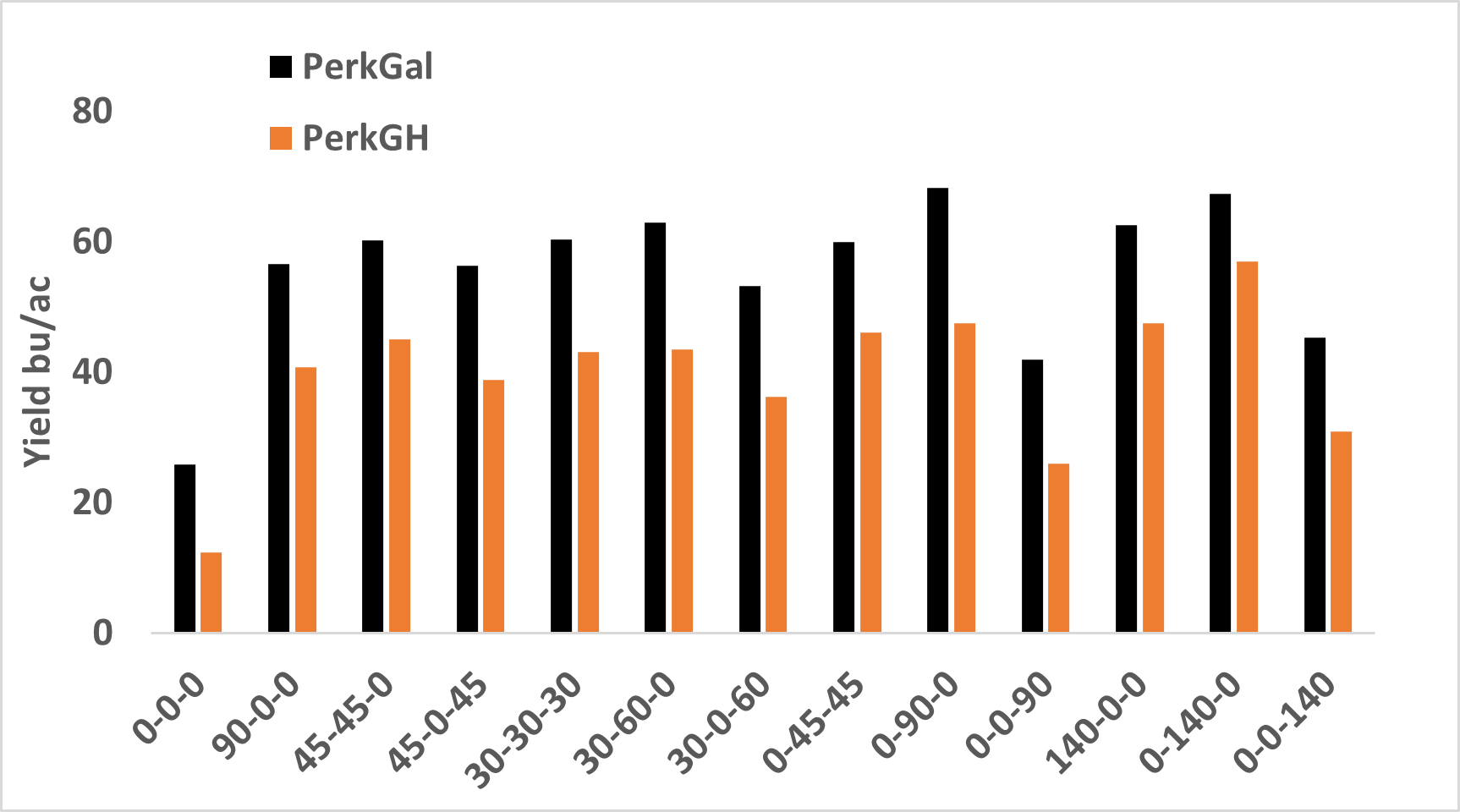

Unfortunately, the spring rains did not fall in 2022 during the critical growth period of jointing. Therefore, the late N application treatment for both projects did not become incorporated into the soil for several weeks after jointing. Thus, note those treatments receiving the majority of N at jointing resulted in lower yields (Figures 1 and 2). Even with the intense drought, both locations yielded well, with yields in the 60 bu/ac range.

The results were similar across locations and cultivars. For each cultivar at each site, stepwise increases in yield were observed as N application moved into the spring, i.e., for the 90-0-0, 45-45-0 and 0-90-0 treatments. Also, for all sites and cultivars, the 0-140-0 treatment significantly out-yielded the 140-0-0 treatment. In other words, both cultivars had their best yield when all N was applied at green-up. Treatments that received some or all N pre-plant performed worse than those receiving the majority of N or all N at green-up.

Figure 1. Grain yield from the Lake Carl Blackwell (LCB) site for Gallagher (black bars) and Green Hammer (orange bars) in the nitrogen timing study. Values along the x-axis represent pounds of N applied at preplant-greenup-jointing.

Figure 2. Grain yield from the Perkins (Perk) site Gallagher (black bars) and Green Hammer (orange bars) in the nitrogen timing study. Values along the x-axis represent pounds of N applied at preplant-greenup-jointing.

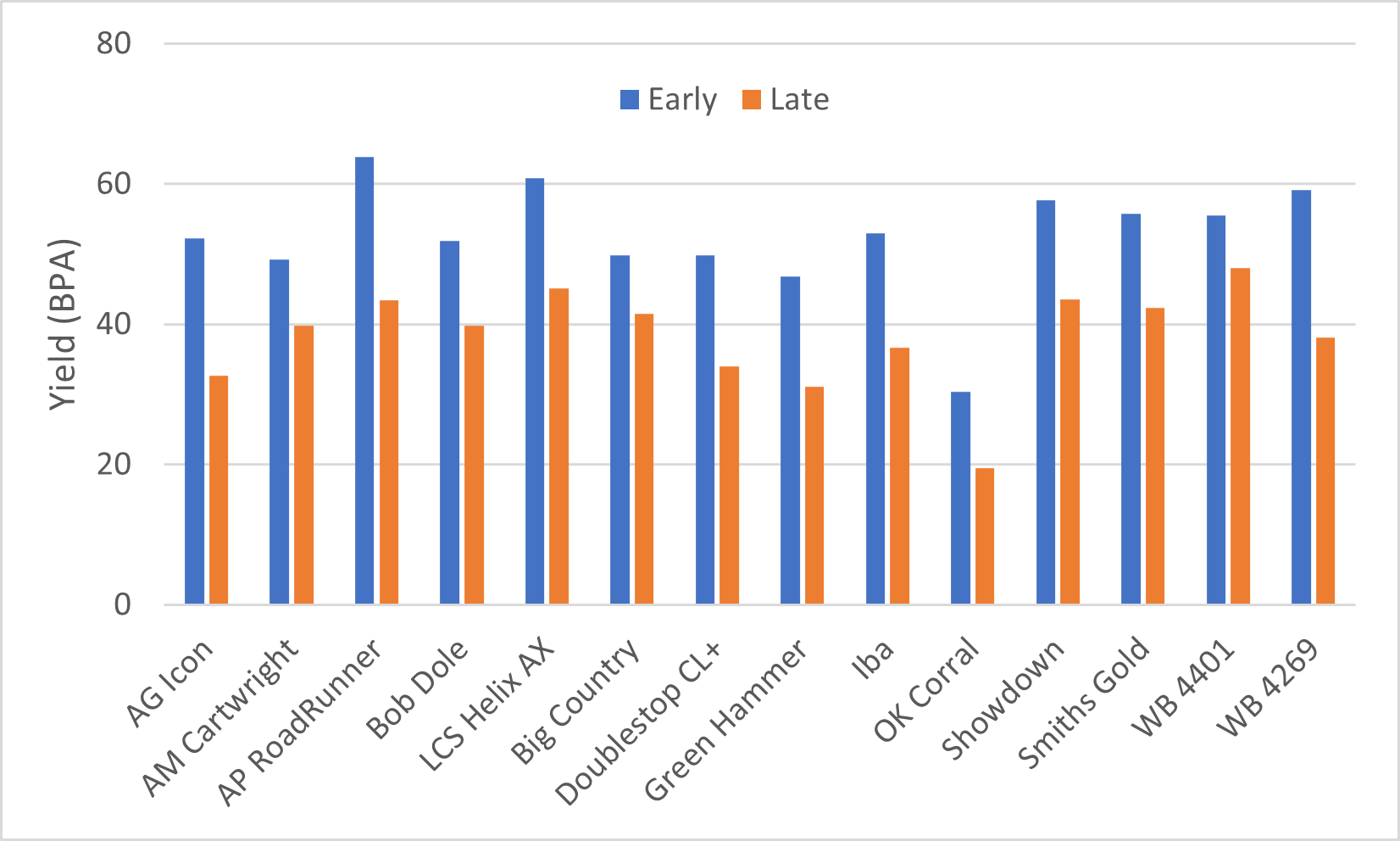

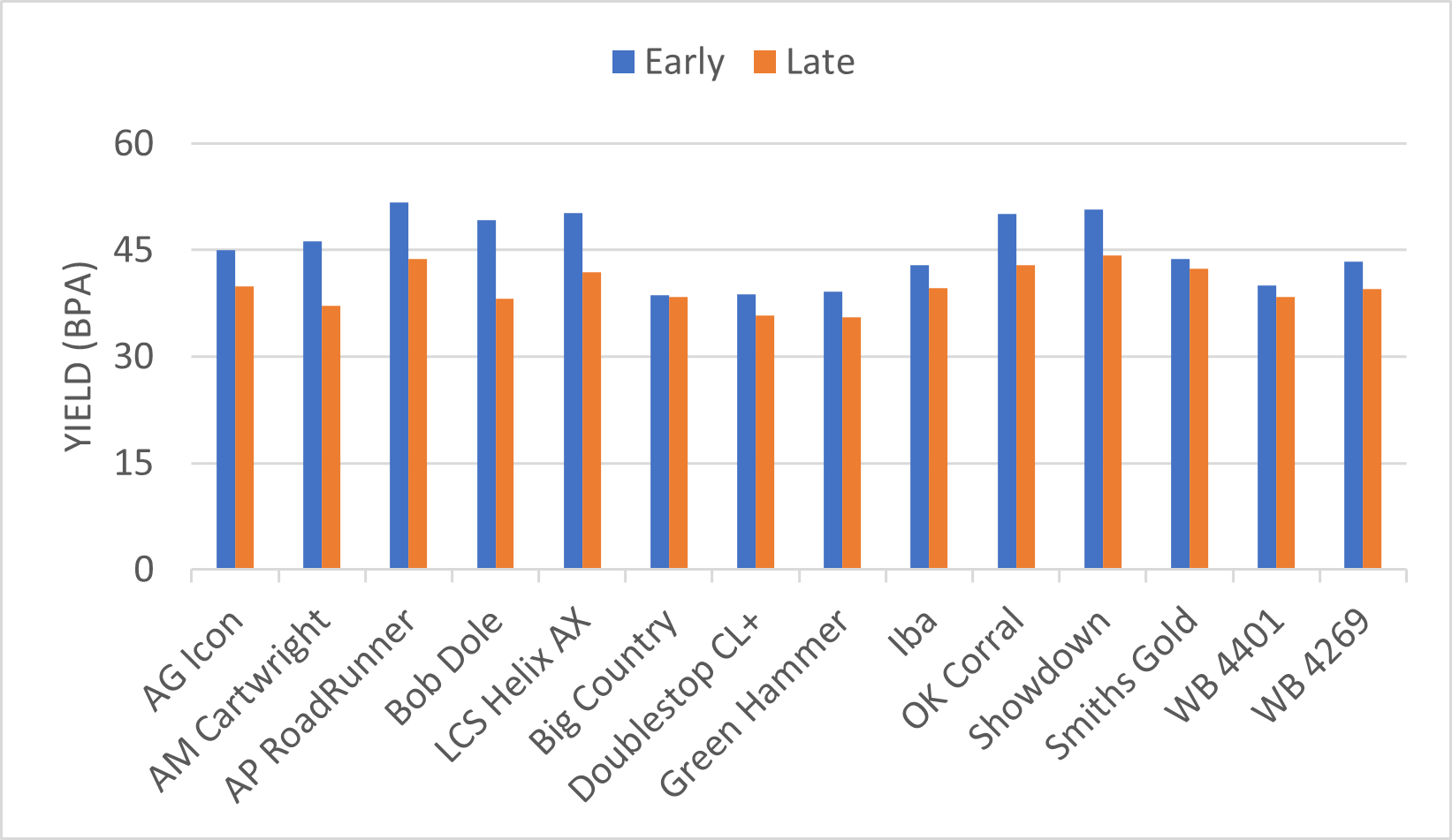

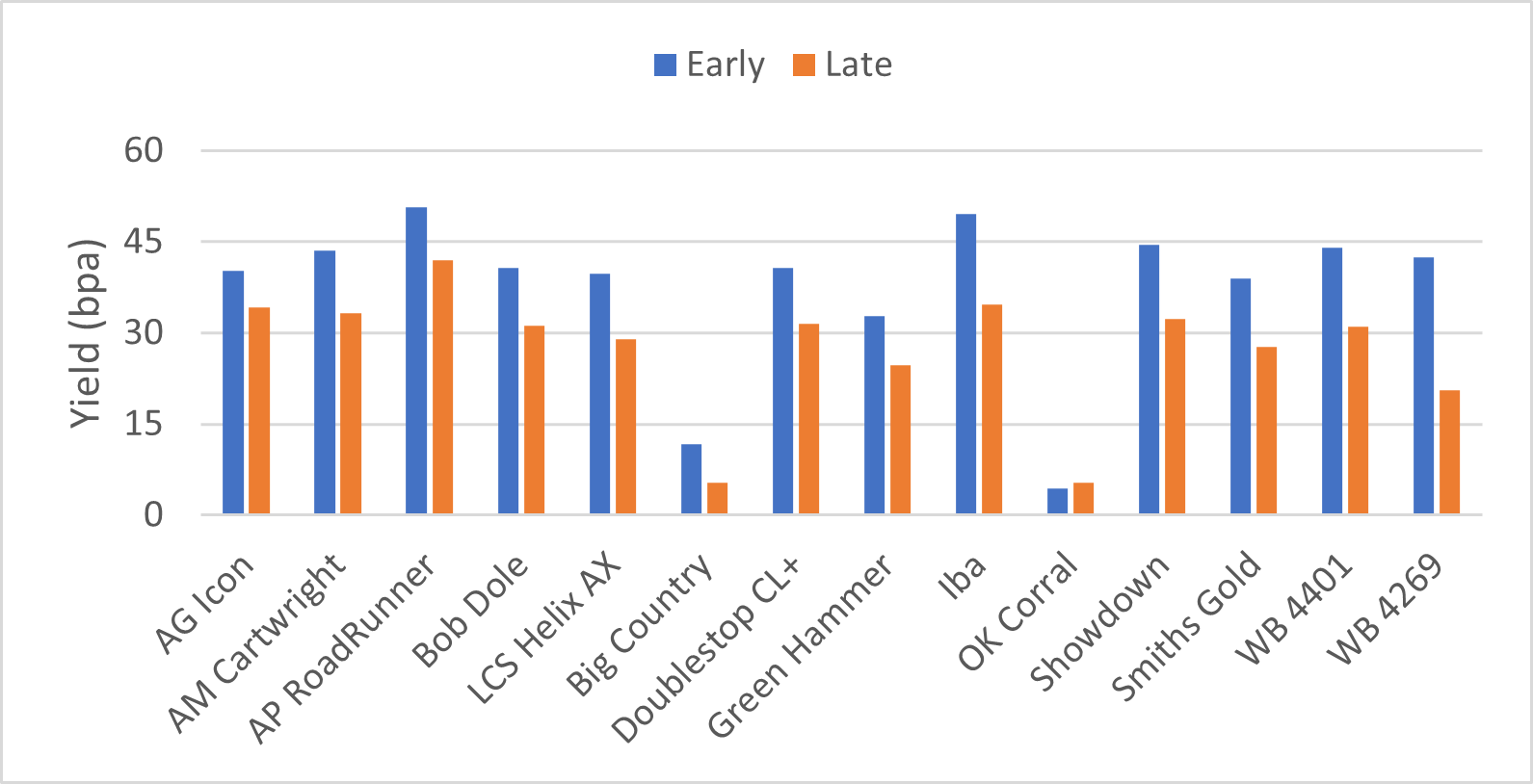

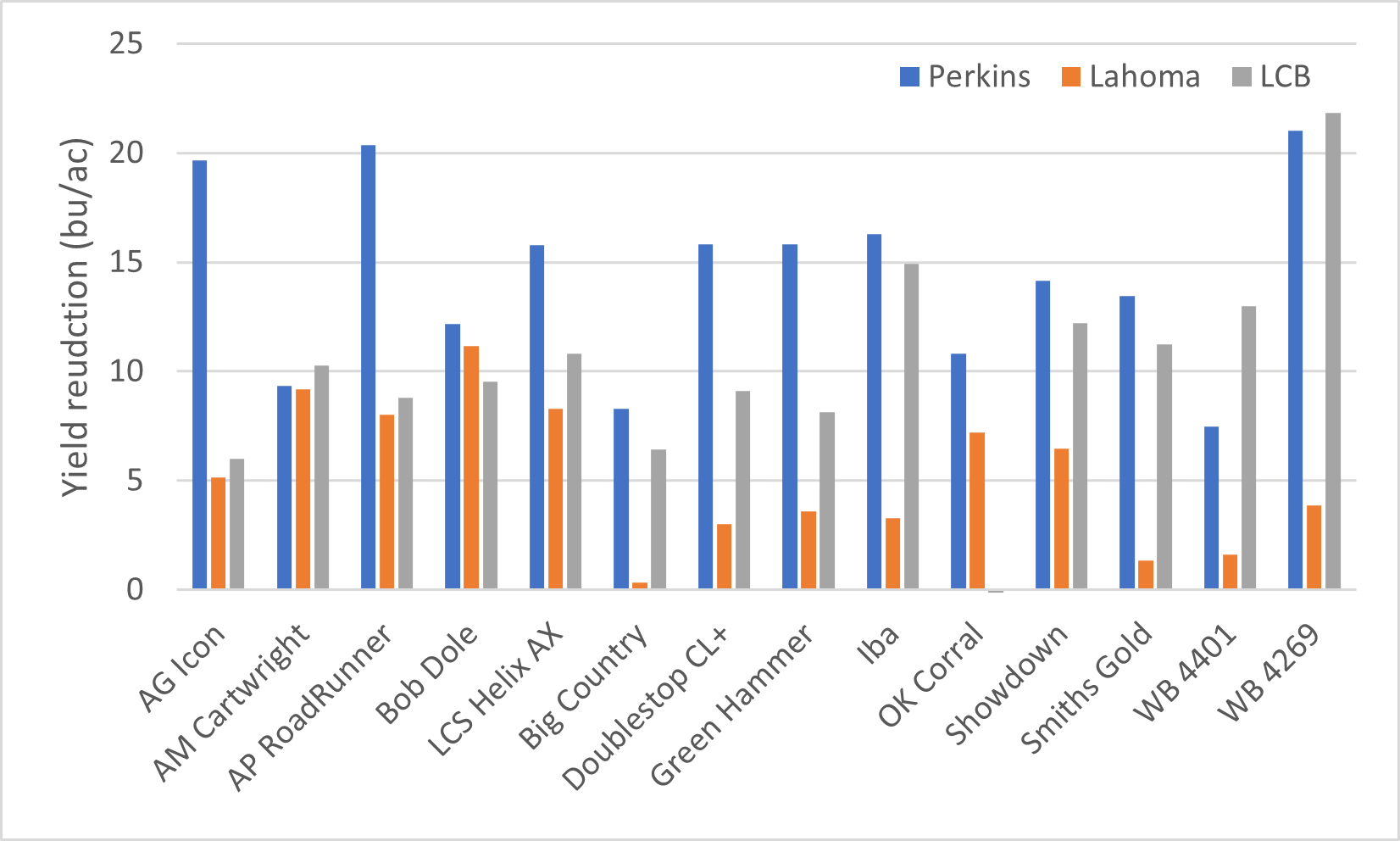

The second project implemented in the 2021-2022 season was the GxN study designed to screen a diverse pool of genetics for preference of early or late applied N. Fourteen cultivars, including seven from Oklahoma State University, were evaluated under two N management schemes: all N applied prior to green-up (early jointing) and all N applied post-jointing (Figure 3). The N rate utilized in this trial was 120 lbs N per acre, applied at three locations (Perkins, Lahoma and LCB). The spring drought had significant impact on this study, as the post-jointing N applications were not incorporated via rainfall until just prior to booting (Figure 4). This resulted in significant declines in grain yield for that treatment (Figures 5-7).

While the 2022 drought impacted the ability of the wheat to respond to the post-jointing N applications, there was still an opportunity to evaluate and interpret the yield difference between the two timings. This data can be seen in Figure 8 where each bar represents the difference in grain yield between the early jointing and post-jointing N applications. It was evident, especially at Perkins where there is a deep sandy soil, that some cultivars were impacted much more by N application timing than others. A representative comparison would be AG Icon versus Big Country. AG Icon suffered a 20-bushel reduction, whereas Big Country showed only an 8-bushel reduction, with both varieties producing 50 bushels per acre with the early N application. AG Icon is generally believed to be early maturing and earlier than Big Country. The question might be asked, would early maturity shorten the window of opportunity to capture the benefit of a post-jointing N application? On the other hand, late maturity should not have played in Big Country’s favor in the season-long drought environment of 2022. Which bears greater penalty? Nonetheless, this sample of cultivars did show the tendency for varying resilience to N deficiency.

This work is beginning to shed light on the impact of cultivars on optimum nitrogen management, but given the diverse nature of Oklahoma weather, more years are needed to better understand this relationship.

Figure 3. Image of the Lahoma GxN trial at the time of green-up.

Figure 4. Big Country post-jointing N and early jointing N treatments at Perkins.

Figure 5. Grain yield from the Perkins GxN study where the blue bars represent early-jointing applied N, and the orange bars represent post-jointing N application.

Figure 6. Grain yield from the Lahoma GxN study where the blue bars represent early-jointing applied N, and the orange bars represent post-jointing N application.

Figure 7. Grain yield from the Lake Carl Blackwell GxN study where the blue bars represent early-jointing applied N, and the orange bars represent post-jointing N application.

Figure 8. Difference in grain yield expressed as early N minus the late N applications across all sites.