OSU Wheat Improvement Team feeds the world

Monday, February 17, 2025

Media Contact: Alisa Boswell-Gore | Office of Communications & Marketing, OSU Agriculture | 405-744-7115 | alisa.gore@okstate.edu

In 1892, A.C. Magruder initiated a soil fertility study to evaluate Oklahoma wheat production. In 1930, H.J. Harper established 10 separate fertilization treatments on these plots. The rest is history.

Wheat research on the Magruder plots continues today, and the Oklahoma State University wheat research program has earned international acclaim for its ability to locate specific wheat genes that contribute to nutrient-use efficiency and disease and pest resistance.

Brett Carver, regents professor and wheat genetics chair in the OSU Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, took over the modern wheat breeding program in 1998, following the retirement of Ed Smith. Twenty-six years later, Carver is one of the most recognized faces nationwide in wheat breeding and genetics.

“I had the idea going into this that we needed to have a more concerted effort for our scientists to work in a more collaborative way rather than in a competitive way,” Carver said. “It’s not unusual for researchers at universities to compete for research funding, but I thought, why don’t scientists just get together and say, ‘This is what we’re going to do?’”

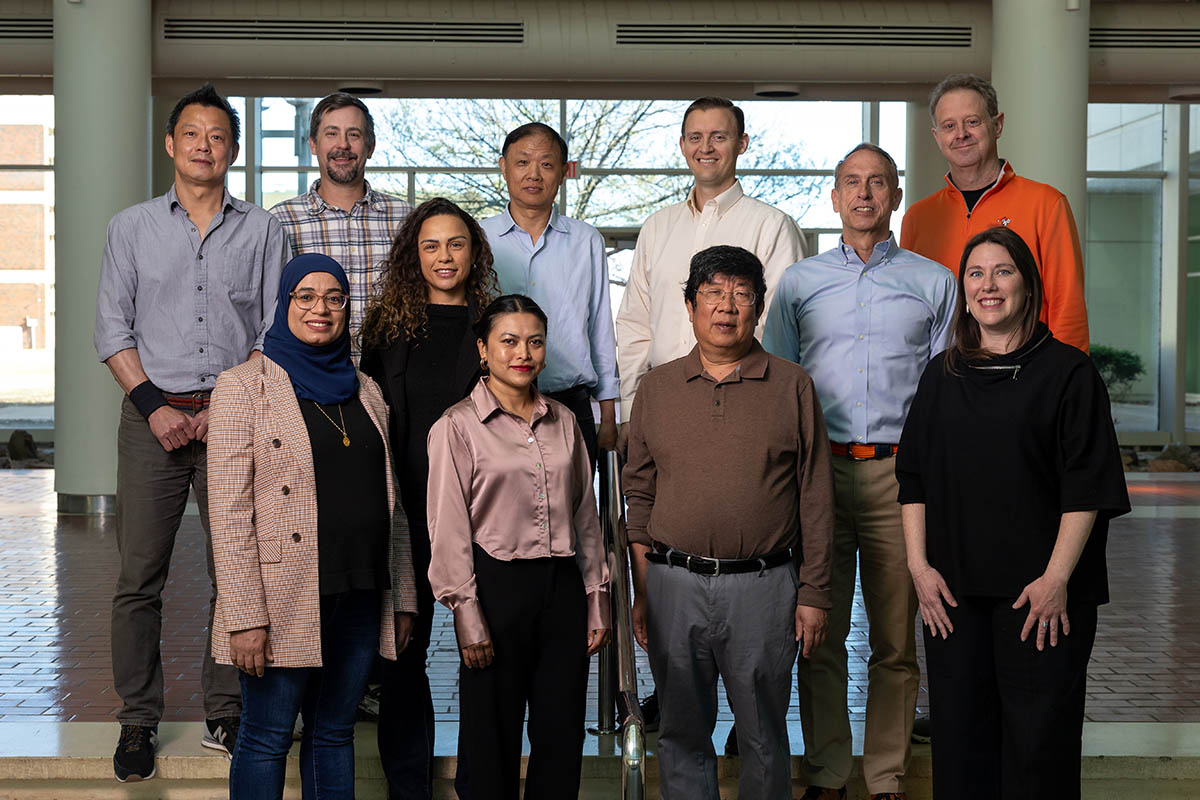

Thus, the Wheat Improvement Team was born. The team of 11 is dedicated to improving protection against 14 or more fungal, bacterial and viral diseases and four insect species. The team also focuses on tolerance to drought and low soil pH, optimizing growth stages for dual-purpose or grain-only wheat production, and improving other agronomic and quality traits.

Navigating the Oklahoma landscape

In 2000, the team identified stripe rust for the first time in breeding nurseries.

“Before then, I had never given stripe rust a thought because it was so novel. Little did I know it would become a full-blown nuisance,” Carver said.

The team released variety OK102 in 2002. That same year, stripe rust hit Oklahoma with a vengeance and decimated OK102.

“I’ll never forget going to a wheat commission meeting in 2002, and a producer looked me straight in the face and said, ‘That’s the sorriest variety I’ve ever grown,’” Carver said. “That’s never what you want to hear. It turned out that it was susceptible to early infections of stripe rust, but we had no real data to go on with the disease until 2001. We knew we had to put more resources into that disease. To date, we haven’t shut it down, but we have a good handle on it now with varieties like Smith’s Gold, OK Corral, Paradox and Big Country.”

The first big breakthrough variety from the WIT team was Endurance, released in 2004.

“It laid the groundwork for the success that was to come later. That variety is still out there today being used in dual-purpose acres,” Carver said. “That was the breakthrough moment for dual-purpose wheat. We had dual-purpose wheat varieties before, but that one raised the bar on how well a variety could tolerate and extend grazing.”

Next came Duster in 2006, a variety with not only grazing tolerance but also Hessian fly and leaf rust resistance.

“Something all too common back then was releasing a variety with leaf rust resistance, then two years later, it’s out there in a lot of acres, but the pathogen has adapted, and you no longer have the same level of resistance,” Carver said. “Duster had such a deep genetic package that the pathogen was not going to adapt to it quickly. To this day, it still has effective resistance.”

The first widely adopted OSU Clearfield variety, Centerfield, was co-released with Duster in 2006, a banner year for OSU wheat commercialization. Like other Clearfield varieties at the time, Centerfield only carried one gene for tolerance to the grassy weed herbicide Imazamox. That changed dramatically in 2013 with OSU’s first two-gene Clearfield variety, Doublestop CL Plus. No Clearfield variety has dominated Oklahoma wheat acres like Doublestop CL Plus, the No. 1 planted variety in Oklahoma since 2022, which offers protection against multiple Oklahoma weeds.

“That was a milestone that took many miles to figure out,” Carver said of the variety. “The challenge was two-fold – breed a two-gene herbicide-tolerant variety with higher yield but with bread quality befitting the hard red winter wheat class. As it turned out, Doublestop CL Plus didn’t just have muster; it gassed the competition, especially in the bakery.”

Digging deeper

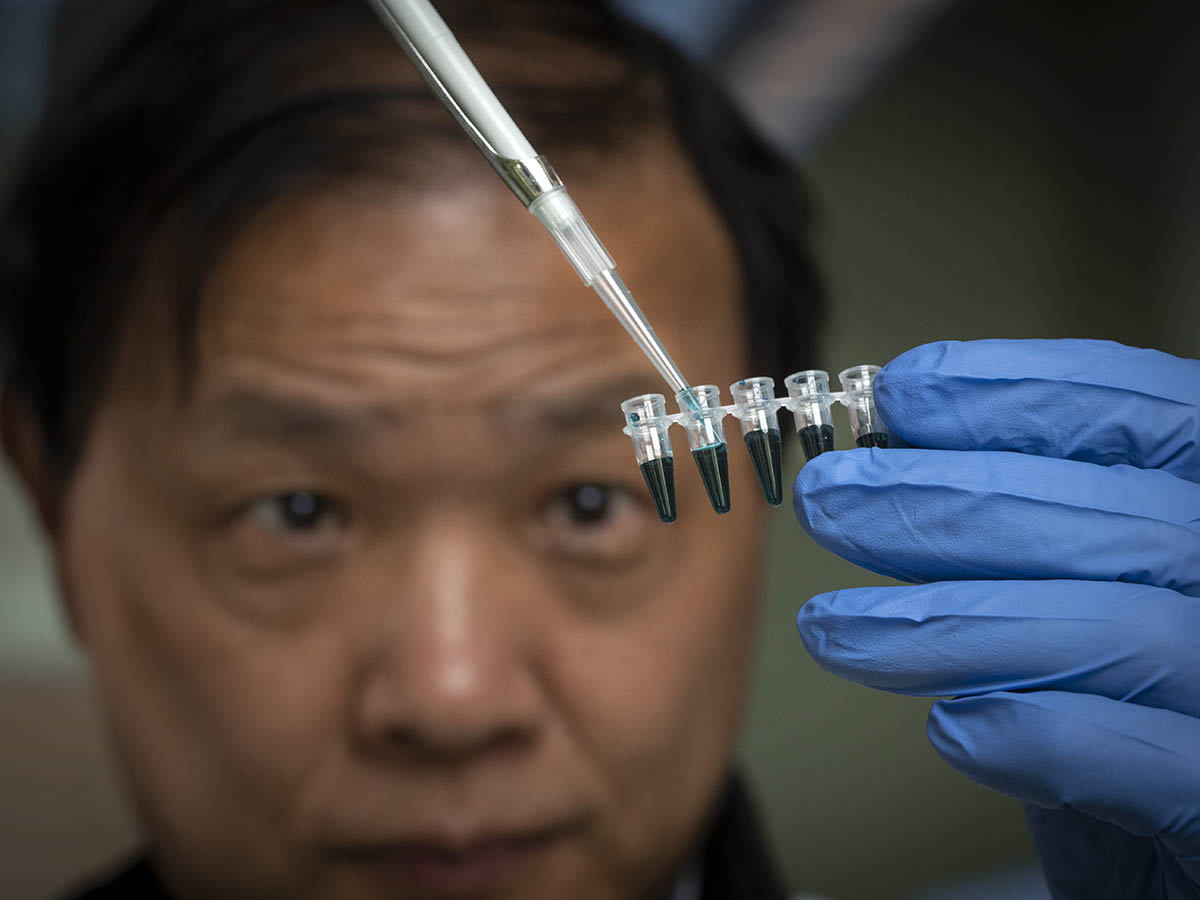

Liuling Yan, regents professor and geneticist in the OSU Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, is responsible for finding the genetic packages that create these varieties. He discovers the functions of a single gene to explain how a gene produces a certain trait.

When realizing that OSU varieties 2174 and Duster exhibited resistance to leaf rust in different ways, Carver asked Yan to find the genes that caused the resistance. That’s when Yan discovered a critical variant of the Lr34 gene, which has become one of the most important disease-resistant wheat genes worldwide. The Lr34ab gene resists leaf rust, stripe rust, stem rust, powdery mildew and barley yellow dwarf.

By detecting multiple variations of the Lr34 gene, Yan created tools for identifying different versions of the gene in wheat varieties. These genetic tools allow scientists to see the entire genetic picture around Lr34.

“Whatever breeding lines Dr. Carver has, we use these genetic markers to tell him which varieties have the resistant gene,” Yan said. “Now, many of the OSU wheat varieties have the Lr34 gene. A wheat breeder can breed a resistant variety with one resistance gene, but it’s going to be a doomed variety somewhere down the road. You have to have genetic diversity.”

A more recent addition to the Wheat Improvement Team is Meriem Aoun, an assistant professor and small grains pathologist in the OSU Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology.

“Like Dr. Yan, my work is in targeting genes, but for me, I want to understand all the genes that we have in hard red winter wheat,” Aoun said. “We determine all the genomic regions that are associated with leaf rust and stripe rust resistance so we can find the critical genes responsible for these traits.”

Aoun works with breeding lines across the Great Plains. She scans the entire wheat genome to see which genes are present. Along with Yan, Aoun designs markers to identify these resistance genes in future breeding lines.

“We have identified so many other genes like Lr46 and Lr77 that are present in hard red winter wheat, but we’ve also identified other gene locations that we don't fully understand yet,” she said.

Education everywhere for everyone

Aoun also plays an Extension role by presenting across the state on wheat diseases in Oklahoma and the appropriate management of those diseases.

Amanda Silva, assistant professor and Extension specialist for small grains, serves as the primary Extension specialist on the team. She coordinates the Small Grains Variety Performance trials in Oklahoma and conducts the applied research and Extension program, which focuses on improving wheat variety traits and crop management strategies.

“I research nitrogen management and seeding rates for late-planted varieties, and I provide recommendations for developing management practices for late-planting and dual-purpose wheat,” Silva said. “I also study nitrogen accumulation within wheat plants to help develop varieties with both high yield and high protein.”

Silva conducts her research at OSU research stations and in fields in partnership with wheat producers. Based on this research, she educates producers on best practices for dual-purpose and late-planted wheat.

“At field days, wheat producers can walk our research fields and see the research we are conducting,” she said.

To wheat-finity and beyond

While the Wheat Improvement Team continues to breed stronger wheat varieties for Oklahoma producers, it also brings to life other unique innovations.

The wheat breeding team began working with a genetic protein called Bx7oe in 2012. The gene was bred with the OSU Gallagher variety, and the three varieties that resulted from the match had a shocking effect.

Flour from OSU’s Paradox, Breadbox and Firebox wheat varieties provides an uncommonly high level of dough strength while maintaining flexibility. The goal is to drastically replace additives over time with natural flour, extending the use and value of hard red winter wheat to the U.S. baking industry.

Anthocyanins give dark-colored foods – such as blueberries, pomegranates and black beans – their color pigment, and anthocyanins have health benefits by creating antioxidants in the human body. The anthocyanin content in red wheat is only about 6 micrograms per gram compared to berries, which have about 20-25 micrograms per gram of anthocyanins.

The OSU wheat breeding team bred a purple wheat from a Romanian wheat program with the OSU Smith’s Gold progeny that was crossed with a white OSU wheat called Big Country. The resulting variety measured about 20 micrograms per gram of anthocyanins. Carver hopes to soon place the new purple wheat variety on the commercial market.

“Whether the priority is enhanced nutrition for consumers or better-adapted varieties for Oklahoma farmers, the OSU Wheat Improvement Team has the expertise to apply and communicate science for all to benefit,” Carver said.

Other members of the Wheat Improvement Team:

- Charles Chen, associate professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, along with Yan, is a molecular geneticist. While Yan discovers the function of a single gene, Chen discovers unique traits in the patterns of genetic makeup across the entire genome. This allows WIT to see the traits they target at multiple levels. More recent additions to WIT are disease specialists Aoun and Xu, who operate at the interface of these two genetic levels, giving WIT a well-balanced genetic profile.

- Brian Arnall, professor and Extension specialist for precision nutrient management, works closely with extension educators and industry personnel to improve nutrient management practices.

- Liberty Galvin, assistant professor of extension weed science and precision weed management. Specializes in early season weed management and herbicide injury assessment for the WIT.

- Xiangyang Xu, plant geneticist with the USDA-Agricultural Research Service, focuses on discovery and introgression of novel biotic stress resistance genes into WIT cultivars and breeding lines, including genes conferring resistance to leaf rust, stripe rust, powdery mildew, greenbug, Russian wheat aphid and bird cherry-oat aphid.

- Kris Giles, professor in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, works in pest management with emphasis on Hessian fly resistance

- Phillip Alderman, associate professor in the Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, is an agricultural systems modeler. Within WIT, he is responsible for the development of novel field-based and modeling techniques for using drone-based phenotyping systems to improve breeding selection efficiency.